Why We Cannot Simply Move on To the Business of Making Zimbabwe Great- The David Coltart Apology

The current conversation on apologies is quite encouraging. Zimbabweans are interested in finding a way towards national healing and reconciliation. The first high profile apology was delivered by David Coltart a white Zimbabwean, in his 60s, on Rhodesian atrocities, his time in the British South Africa Police (BSAP) and his role in sustaining an unjust system of government which discriminated against black people.

BSAP Officials during the war of independence.

Credithttp://www.imgrum.org

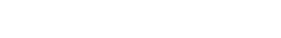

The Coltart apology is not a perfect. At one point, he uses the problematic phrase “violence on both sides” and goes to great lengths to downplay his position in the BSAP. He was not some low-level subordinate following the orders of his superiors. He was part of the superiors. In his best-selling and yet, poorly titled book, The Struggle Continues: 50 years of tyranny in Zimbabwe he provides important background on the occasion in which he buried a black guerilla in a mineshaft, “After two weeks of going through the same routine I decided that I should see how and where my subordinates were burying the bodies.” page 80.

Even with these problems, the apology, is an important step in our national healing process. By acknowledging specific acts of violence against his fellow countrymen, Coltart has provided us another opportunity to seek redress for victims and survivors.

In this excerpt from David Coltart’s apology published on Facebook on January 27, 2018– He wrote

“I am grateful to God that I was never involved in any direct combat and have never killed anyone. There was, however, one extremely horrible incident where I was required to dispose of the dead body of a guerrilla (who had been shot and killed in a gunfight with Rhodesian forces) down a mineshaft. I disclosed this incident in my book precisely because I believe we all have an obligation to share the truth and to not spare ourselves in doing so.”

In his book, Coltart describes the dumping of this black guerilla in greater detail. He writes that the young guerilla looked as though he could have been his age mate. During the dumping, the body “caught on to a jagged flap” as if the young man was protesting this unceremonious disposal of his body. He thrown down without a prayer and a sack of lime –not sand- was poured over his body.

There are many stories of families whose sons and daughters never returned from the war. From Coltart’s apology we now know with even more certainty that there are many mass graves around Zimbabwe and that perhaps we can give some families a final consolation. As I read the apology, I imagined that somewhere is a mother who probably went mad because she has no idea what happened to her son. Somewhere is a friend of the young fighter who blames himself for not trying harder to not only save his friend’s life but also bring back his body home for burial. If this young man was a father, then there are children who have no idea how their father died. Maybe, they have spent their adult lives mad at him because they think he went to Zambia or Mozambique were made wealth with his second family. Maybe they grew up to be bitter adults who do not love their country because their country killed their father. I hope that they are well adjusted adults who have been able to heal from this loss.

About 600 bodies were recovered from this particular mine (this is not the one were David Coltart buried a body). There are a few organizations engaged in exhuming mass graves and providing proper burials. You can read more here

For most young Zimbabweans, there is a need or an urgency to get on with the business of rebuilding the economy and burying the past. Our challenge is that the past is living. Addressing the past can be good future economic social prosperity. This man who was buried like an animal would have been 60 or 65, that is not too old. That means that his family who have carried the burden of his loss are still alive. Think of it this way. Knowing what we know about some traditional families maybe they sought the help of a N’anga who told them that it was an aunt or an uncle who had forced the young man into the wilderness. Now, maybe there is a broken family, a sister and a brother who have not spoken to each other for over 37 years because they have blamed each other over the death of this young man. They have come to think that they are cursed, because, surely if their family had not been cursed, they would have been able to find his body and bury him. And, maybe his mother failed to mother her remaining children because she has never been able to get past her son who has no grave. Human beings need to bury their loved ones and to see their graves. It is not likely that we will be able to find this young guerilla’s family. I doubt it but one can be hopeful.

However, we can use these stories to engage in the practical matter of properly reburying our dead. Maybe as others open up we will hear stories of survivors who are still looking for their way home.

I am grateful to David Coltart for documenting an uncomfortable and inconvenient truth.

Author

Chipo Dendere

More from Coltart’s book

Coltart page 80: David Coltart details some of his duties as a member of the BSAP

Discussion